The Barbary Lion: England’s Silent Sentinel

Once the roar of a lion echoed through the dense forests and rugged mountains of North Africa. Today, that roar lives on — not in the wild — but in stone and bronze, and in the very heart of a nation (London).

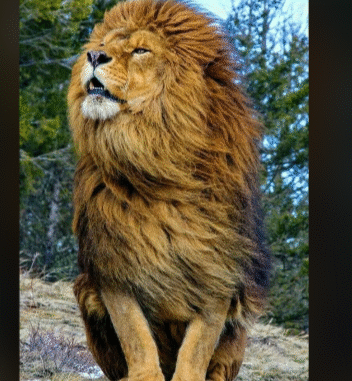

The Barbary lion (Panthera leo leo), also known as the Atlas lion, once roamed the mountainous and desert regions of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Renowned for its immense size and dark, luxuriant mane, the Barbary lion was the largest of all lion subspecies. Males could weigh over 500 pounds and measure more than 11 feet in length. Celebrated in Berber folklore and feared in ancient Rome, it was a creature of unmatched majesty.

England’s connection to the Barbary lion began in the 12th century, when crusaders and diplomats brought the lions as royal gifts. These beasts became symbols of monarchic power. By the 13th century, they were housed in the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London, intimidating dignitaries and captivating the English court. Their powerful imagery inspired the heraldic ‘Three Lions’ crest, made famous by Richard the Lionheart in the late 1100s.

Over time, the Barbary lion became an enduring emblem of English identity. From royal coats of arms to modern sports, including the crest of England’s national football team, the lion came to represent bravery, leadership, and legacy.

Tragically, this king of beasts fell victim to human greed and encroachment. By the early 20th century, the Barbary lion was extinct in the wild. The last confirmed sighting occurred in the Atlas Mountains in the 1940s. A few descendents survive in captivity, mainly in Morocco and Europe, kept alive through limited breeding programs.

Yet the memory of the Barbary lion lives on. At Trafalgar Square in London, four colossal bronze lions guard the base of Nelson’s Column. Sculpted by Sir Edwin Landseer in 1867 and modeled on lions from the London Zoo, they are believed to have been inspired by the Barbary lion. Each lion is over 20 feet long, lying in solemn repose, their eyes ever watchful over the city. These are not mere statues. They are icons of power, echoes of an empire, and tributes to a once-living legend.

Across the Mediterranean in Ifrane, Morocco, a granite sculpture of a Barbary lion stands in quiet tribute. Carved by a German prisoner in the 1930s, it commemorates the lion’s reign in the Maghreb and symbolizes national pride. Though oceans apart, both sculptures share a cultural reverence for the Barbary lion’s vanished grandeur.

To the English people, the lion is more than a symbol — it’s a story of continuity, courage, and national pride. Its image graces coins, military insignias, and school crests. It reminds the nation of a time when its reach spanned the globe and when the lion truly was king.

Today, conservationists in England and Morocco seek to preserve the lion’s genetic legacy, tracing bloodlines and supporting breeding efforts. Meanwhile, cultural revivals in literature, education, and public art are reawakening interest in the Barbary lion, keeping its spirit alive for future generations.

Though silenced in the wild, the Barbary lion’s roar echoes in stone and bronze, in hearts and heritage. England’s national animal, once feared and revered, remains a potent emblem of power, a ghost of glory, and a call to conscience.

Leave a Reply